Diabrotica undecimpunctata, Acalymma trivittatum, A. vittatum

As a gardener, it’s a real bummer when pesky insects come along and munch on the results of all your hard work.

And when it comes to bumming out a gardener after going to town on their crops, cucumber beetles are quite talented.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Pretty in appearance, yet pretty annoying in behavior, cucumber beetles are not pests you should merely tolerate, lest you wish to jeopardize your cucurbits.

During an infestation, your crops can sustain feeding damage, suffer from stunted growth, and even contract diseases.

Therefore, it’s critical to have some pest management strategies in your back pocket, front pocket… or even your side pocket, if you happen to be clad in cargo shorts.

This guide will tell you everything you need to know about cucumber beetles, detailing their appearance, their life cycle, the damage that they inflict on plants, and how to manage them.

Take heed – your cucumber salads, pumpkin breads, and other melon or gourd-based dishes may very well depend on it.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Cucumber Beetles?

Cucumber beetles aren’t merely a single species, or even a single genus.

Rather, they’re certain members of the Acalymma and Diabrotica genera of Chrysomelidae that consume from cucumbers and other cucurbits, aka gourds.

Cucumber beetles won’t only plague members of the Cucurbitaceae family, although cucurbit consumption is definitely what they’re most known for.

They’ll also go after beans, peas, eggplant, potatoes, fruit trees such as apples and pears, and even certain landscape ornamentals.

Identification

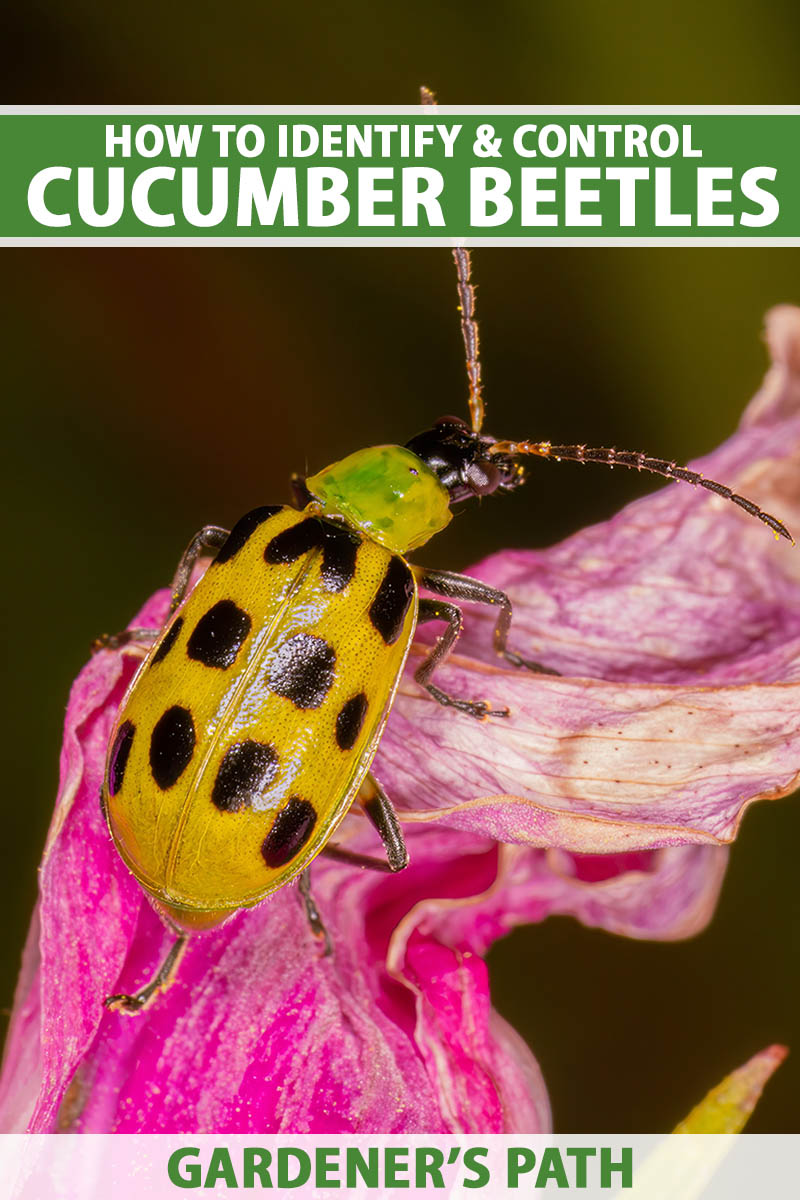

The two most common kinds of cucumber beetle – the ones that you’ll most likely have to deal with – are the spotted and striped varieties.

Both lay oval-shaped, yellow to orange eggs, and the cream-colored, wormlike larvae of both have dark-colored heads and a body length of about half an inch.

The adult forms of both have black heads with yellow to green thoraxes, and are about a quarter-inch long.

The differences between them are right there in the names.

The spotted Diabrotica undecimpunctata has a yellow-green abdomen that’s covered with 12 black dots.

Its striped colleagues have the same yellow-green abdomen, but they sport three black longitudinal lines instead of spots.

The exact species of striped cucumber beetle depends on your location.

West of the Rocky Mountains in North America, you’ll primarily run into the western striped cucumber beetle, or Acalymma trivittatum.

To the east of the Rockies, you’ll most likely run into the regular ol’ striped cucumber beetle, or A. vittatum.

Life Cycle

There are minor life cycle differences between species and locations, but here’s a general outline of the process.

Let’s start with the eggs, which are laid in spring to summer in clumps of 25 to 50 at the base of host and non-host plants alike, as well as in the soil.

A few weeks later, the larvae will hatch from their eggs to consume roots and stems.

After a few more weeks of feeding and maturing through instars, the larvae will burrow into the soil to pupate.

About 40 to 60 days after the eggs were initially laid, adults emerge from the soil to either feed on nearby flora or migrate north to feed.

Depending on how cool the climate is, there could be one to three generations each growing season.

The year’s final generation of adults overwinters in adjacent plant detritus, nearby woodlands, or the soil until the start of the next year’s growing season.

Damage to Plants

What does this mean for your garden? Well, all of this munching doesn’t exactly leave your crops in the best shape.

Larvae take bites out of the roots and lower stem tissues of plants, which can stunt growth or kill young specimens outright when populations are large enough.

Even worse are the adults, who have a broader culinary palette – they’ll consume leaves, blooms, fruits, and even pollen.

Besides somewhat neutering a plant’s reproduction by reducing fruit set and interfering with bee pollination, this feeding can cause significant defoliation and reduced fruit aesthetics.

As you can imagine, missing bits of tissue are pretty bad for an organism, where both health and aesthetics are concerned. But that’s just the physical feeding damage.

As they feed, cucumber beetles can pick up and subsequently transmit a plethora of disfiguring, yield-reducing, and potentially fatal diseases such as squash mosaic virus, muskmelon necrotic spot virus, and Fusarium wilt.

An especially significant and typically fatal illness is cucurbit bacterial wilt, which is caused by Erwinia tracheiphila bacteria and more commonly transmitted by striped cucumber beetles, rather than their spotted brethren.

This disease results in wilting, leaf discoloration, and death, all in a matter of days.

To diagnose bacterial wilt, snip a suspect stem and cut it in half crosswise. After holding the cut halves together for 10 to 15 seconds, slowly separate them.

If the stem is infected, a mucus-like bacterial ooze will hang between the two ends, with an appearance not unlike runny mozzarella.

Control Methods

Trying to stop these pests from turning your beautiful, tasty crops into their own personal chow? Totally understandable.

But first and foremost, you’ll need to keep a sharp eye out for these pests, regardless of the control methods you plan to use.

Regularly inspect your plants for evidence of their presence, especially when new leaves are growing in the cotyledon stage.

Aside from seeing the adults, feeding damage and clusters of yellow to orange eggs are additional signs of an infestation to be on the lookout for.

To make the pests come to you, place traps early in the growing season. For a set of non-toxic, long-lasting, and poison-free traps and lures, behold these bad boys from Arbico Organics.

Now for some control counsel:

Cultural

How you grow and care for your plants can make a huge difference in pest management.

Aside from properly cultivating each of your garden specimens according to its specific needs, there are certain forms of control that don’t involve setting traps, releasing beneficial bugs, or sprays.

Particular plant varieties are less appealing to cucumber beetles than others.

For example, the cucumber cultivars ‘Liberty’ and ‘Wisconsin SMR-58’ aren’t very appetizing to the pests, and neither are the ‘Makdimon’ and ‘Rocky Sweet’ varieties of cantaloupe.

Much like pawns shielding the king in a game of chess, trap crops – i.e. plants that certain pests find especially attractive – can be used to attract enemies away from your more important plantings.

When you think of trap crops, you’re probably imagining plants such as dill or marigolds.

But in the case of trapping cucumber beetles, you can also place other, less-important members of the Cucurbitaceae away from your more critical cucurbits.

‘Blue Hubbard’ squash is a go-to gourd for using as a trap crop around the perimeter of cucurbits. This variety is exceptionally attractive to cucumber beetles, making it the perfect lure!

After cucumber beetle populations have grown on your ‘Blue Hubbard’ squashes or other trap crops, it’s essential to spray them with an insecticide to halt their advance towards the rest of your garden.

Technically, you have other options besides sprays – some commercial growers destroy pests in trap crops with weed flamers, while the mad scientist types may suck up the pests with large backpack vacuums.

Both of these methods may be overkill for most home gardeners, but they are definitely a lot more fun.

Weeds can also serve as hosts for these pests, so be hyper-vigilant about weeding in and around your garden. An un-pulled weed today could very well become home to a cucumber beetle colony tomorrow.

A heavy layer of mulch around established specimens can discourage beetles from laying eggs. If you have access to herbicide-free straw mulch, it can help to keep populations of these pests down and slow their movement between plants.

Be sure to harvest yields promptly and before they hit the ground, clean up nearby plant detritus, and regularly rotate the placement of crops from different families.

The first two tricks will reduce potential overwintering sites, while the latter throws a wrench into the pests’ life cycle.

Specimens infected with bacterial wilt should immediately be removed from your garden and destroyed to halt further disease spread.

If this disease is particularly worrisome in your area, the cucumber cultivar ‘County Fair’ sports some natural resistance.

Physical

In spring and fall, a light tillage of the soil can make short work of eggs and larvae.

For a physical barrier, consider protecting your plants with floating row covers, making sure to put them out before cucumber beetles are expected to emerge in your area.

You may wish to consult with your local agricultural extension to get a handle on the typical timing.

The standard advice has been to leave these covers on until your cucurbits have started blooming. An asterisk, though: this may delay the transmission of bacterial wilt, but it won’t necessarily eliminate it.

Research on muskmelons at Iowa State University found that delaying the removal of row covers by 10 days post-bloom protected plants from bacterial wilt for the entire season.

These trials actually reduced or entirely eliminated the need for insecticide sprays.

But since your plants will most likely need pollination, it may require introducing bumblebees or hand-pollinating under the row covers.

Some organic growers do this by renting commercial bumblebee hives and placing them under cover.

However, this may get expensive or prove to be unavailable in your area, and it would require shading the hives with cardboard, or perhaps a laundry basket.

Plus, bee stings aren’t at all fun and additional training may be required if you aren’t an expert beekeeper already.

Another option is to just open the row cover ends when plants start to bloom, but this runs the risk of allowing the bugs some limited access to your crops along with the pollinators.

Choices, choices…

A quick note, for those unfamiliar: hand pollination is when a gardener manually transfers the pollen from a male flower to the ovaries of female blooms, oftentimes with the aid of small, slender tools such as brushes or cotton swabs. If done correctly, hand pollination can yield fruits without the aid of insects or wind.

For some guidance, check out our guide to hand-pollinating pumpkins.

Biological

In the gardening world, “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” roughly translates to: “the pest of my pest is my pal.”

Beneficial insects such as ladybugs, assassin bugs, and green lacewings will hunt, kill, and eat cucumber beetles with extreme prejudice.

For a selection of beneficial, beetle-bashing bugs, check out this lineup of ’em at Arbico Organics.

For some below-ground backup, beneficial nematodes can help control cucumber beetles in the soil-bound larval stage.

Containing millions of Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, packages of NemaSeek beneficial nematodes are available from Arbico Organics.

Organic Pesticides

If you find that at least a quarter of your younger plants are infested with two or more beetles each, then it may be time to apply an insecticide.

With older plants, you can monitor for the death of leaves. If you find that a quarter or more of the foliage is gone, then you should apply an insecticide.

An effective low-impact and organic insecticide to use is neem oil, which is available from Bonide via Arbico Organics.

Spray every seven to 14 days, or every five to seven days if an infestation is heavy.

Neem oil can adversely affect bees, so be sure to spray when plants are not in bloom, and when bees aren’t out and buzzing about.

Another organic insecticide that you can use is kaolin clay. When applied to leaves, it leaves a residue that sticks to insects, which disorients and irritates them.

Applications of kaolin clay won’t provide full control on their own, but they work well as part of an integrated pest management system.

Surround WP, a wettable powdered form of kaolin clay that’s specialized for agricultural use, is also sold by Arbico Organics.

The clay may be mixed with water and then sprayed where it’s needed.

If you know that your soil is infested with larvae, you can treat it with spinosad – an organic mixture of compounds derived from bacteria.

One formulation, Monterey Garden Insect Spray, is a broad-spectrum spinosad insecticide that’s available in various volumes from Arbico Organics.

For a more rapid control response, sprays of pyrethrin or azadirachtin insecticides directly applied to infected tissues are effective. But they can also take out beneficial insects, so be mindful.

Chemical Pesticides

Since broad-spectrum insecticides are very potent against many different bugs, caution and moderation in their usage is essential.

And of course, you should always heed any product warnings and follow all application instructions when using chemical treatments in the garden, if you opt to do so.

Does Your Garden Need Debugging?

Consider this guide a “patch” for your cucumber patch – or any of your other cucurbits, for that matter.

Heck, these tips help with any plants that cucumber beetles could infest, of which there are many.

With some prevention practices in place and control measures in reserve, you can keep your garden safe from cucumber beetles for years to come. And if mistakes are made and crops are lost, fear not. Losing a battle doesn’t equal losing the war!

Any questions on pest management still lingering? Experiences that you’ve learned from? Put ’em in the comments section below!

Want to learn how to manage more beetles that may infest your precious vegetable crops? Check out these guides: