Trying to choose a ginkgo tree for your landscape?

Along with size, form, and growth rate, don’t forget to consider one of the most important factors in selecting a Ginkgo biloba: its biological sex.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

When it comes to members of the plant kingdom, it’s often easy to forget that they have male and female bits, too.

Nothing quite as recognizable or explicit as what animals have, but they’re there.

And while many plants are monoecious – having male and female parts on the same specimen – ginkgos are dioecious, with entirely separate male and female plants.

With many dioecious plants, you can pretty much use the males and females interchangeably throughout the landscape. But if you were to do that with G. biloba, you’d be making a grave mistake.

Well, maybe “grave” is too strong a word. But you’ll certainly be kicking yourself and thinking: “Man, this stinks.”

For the rundown on male versus female trees and what each can do for your landscape, read on.

But don’t worry – for Ginkgo Sex Ed, you won’t need your folks to sign a permission slip like your middle school health class may have required. No awkward or mentally scarring videos here!

Here’s the curriculum:

What You’ll Learn

A Brief Ginkgo Primer

Hardy in USDA Zones 3 to 9, G. biloba is a deciduous tree that typically reaches heights of 50 to 80 feet with a spread 30 to 40 feet, although its millenia-long lifespan under ideal conditions may allow for even greater dimensions.

With green, fan-shaped leaves that turn a gorgeous yellow in fall, the beautiful tree provides some decent shade throughout spring and summer.

These trees are quite ancient, with the oldest discovered fossils dated to be more than 200 million years old.

Informally known as “living fossils,” they’ve hardly changed since the days of the dinosaurs.

As the last surviving member of the ginkgos, G. biloba held out in select pockets of China before humans came along and began to cultivate it elsewhere.

With many geological epochs of adaptation and survival under its belt, G. biloba is super tough, wielding tolerance for air pollution, heat, drought, tight planting spaces, and most soil types.

It doesn’t typically face many pests or diseases, making it one of the most resilient ornamental trees available.

In the landscape, ginkgos are valued for use as specimens, shade trees, urban plantings, and even bonsai!

Similarities Shared by All Ginkgos

Many living organisms exhibit secondary sex characteristics, i.e. sex-distinguishing traits that aren’t directly involved with reproduction, such as sex-specific plumage colors, milk-producing mammary glands, and especially prominent Adam’s apples.

Not ginkgos, though. Aside from the parts directly involved in reproduction, there’s not really an obvious anatomical difference between male and female specimens of the same variety.

The purely ornamental and structural parts of the tree are essentially identical across the sexes.

And here’s the kicker: since the trees take at least 20 years or so to bear reproductive structures for fruiting, it’ll take a G. biloba grower at least two decades to visually tell male and female trees apart.

But plant nurseries worth their salt should label or otherwise let you know of a specimen’s sex before you purchase it.

If you urgently need to know the sex of a young specimen, you could opt for genetic testing.

But that might very well be an expensive hassle that’s either difficult or impossible for the home grower to obtain. Prior to purchase, make sure the vendor knows and informs you of your purchased specimen’s sex!

Differences

If this were a middle school human health class, this would be the point in the sex ed lecture where certain members of the class might erupt with giggles and “ewww”s, especially if there were diagrams involved.

Thankfully, discussing the differences between male and female ginkgos isn’t as awkward.

Male Plants

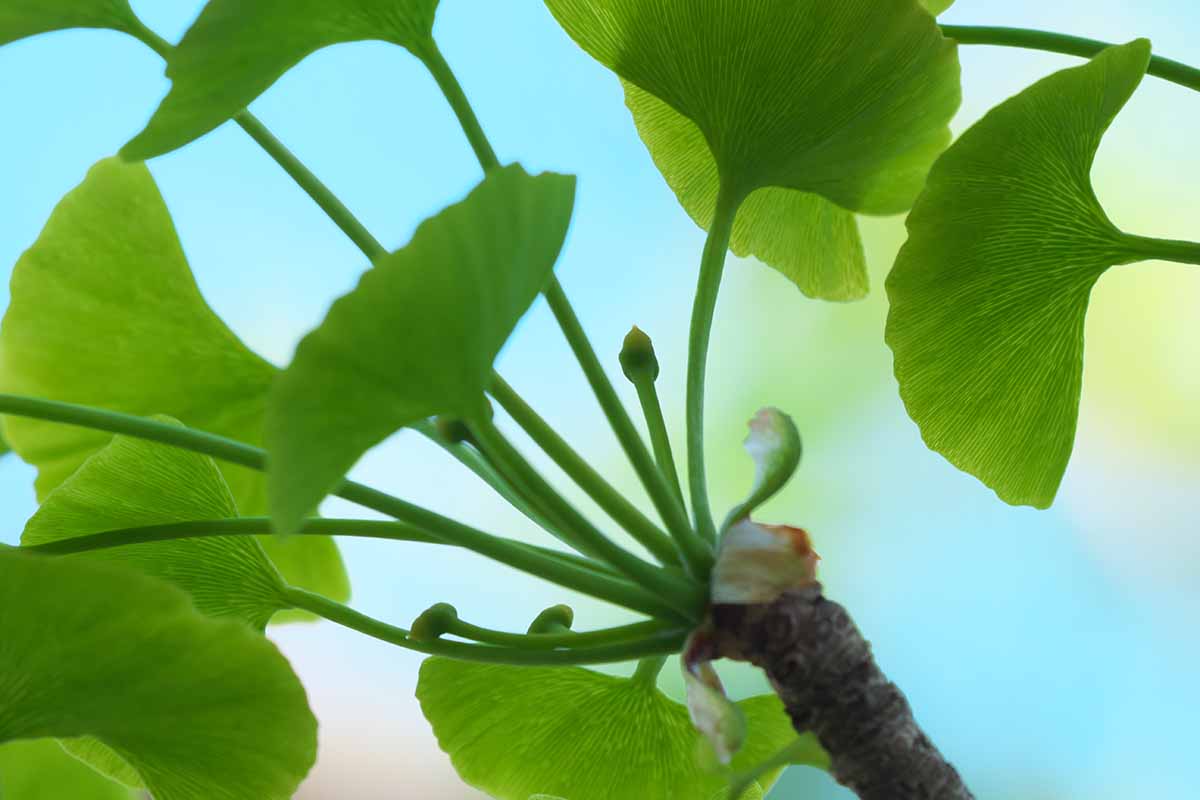

Technically a gymnosperm, G. biloba begins its reproductive cycle with the male trees, which form clusters of green, cylindrical, one-inch-long catkins in spring.

Spotting these catkins is the gendering giveaway, your cinematic “It’s a boy!” moment.

After their formation, the catkins produce pollen, which the wind carries away.

Some of it is carried away to nowhere important, perhaps ending up on a car windshield or inside the sinuses of a seasonal allergy sufferer.

But other bits of pollen have a more important destiny, and the wind whisks them away towards a lady ginkgo.

Female Plants

While male plants were developing their catkins, the females were forming olive-esque ovules. As the pollen is released, the ovules secrete a liquid that helps to catch the pollen.

Once pollen is caught by an ovule, it develops into a sperm-releasing male gametophyte, which fertilizes the female gametophyte within the ovule.

Post-fertilization, these ovules produce almond-like seeds, which are coated in fleshy, yellow to orange pulp.

Upon dropping to the ground, these fruits often break open in a messy fashion, releasing a malodorous scent that’s akin to vomit, feces, and/or rancid butter.

Typically, G. biloba produces seeds in a 1:1 ratio of males to females.

Meaning, if you were to take one of a tree’s seeds at random and plant it, you’d have a 50:50 shot of ending up with a specimen of your preferred sex.

Which should you prefer, though? Let’s find out.

But first…

An Interesting Intersexual Interjection

In the absence of a nearby ginkgo of the opposite sex, G. biloba has actually been known to change sexes, albeit only slightly.

In rare cases, solitary male specimens have been observed to produce a single ovule-producing female branch, which it can pollinate all by itself. This acts as a reproductive backup plan in the case of having no adjacent trees available to breed with.

Females can do the opposite of this by producing a catkin-flowering branch among the seed-producing ones. But this is even more rare than male sex-changes.

Why do lady ginkgos perform this action less often? Well, from an evolutionary standpoint, here’s a theory that makes a bit of sense:

In a jam, an intersexed male can fertilize its lady parts while still having ample pollen to breed with other trees. But a female in similar circumstances can pollinate a vast amount of its own ovules with just a couple of catkins, severely limiting the amount of external fertilization it can receive.

With inbreeding comes low genetic diversity, which reduces adaptability.

If everyone’s genetically similar, then an environmental stressor that may typically wipe out some of a population is now more likely to wipe out all of the population, since the general population lacks potentially-useful genetic differences that could help the species as a whole survive.

Isn’t nature fascinating? Plus, the rarity of intersex G. biloba makes it all even more exciting, in my opinion.

So Which Should You Plant?

For landscapers, gardeners, or anyone who simply wants a nice ginkgo on their property, the answer is obvious: a male tree.

Why? Because the females produce and drop messy, nasty-smelling fruits that are considered a rank affront to olfactory receptors everywhere, at least by many people.

If you’re a ginkgo breeder, though, or otherwise need to produce some G. biloba seed to harvest, then you’ll obviously need some gal ginkgos to go along with the guy.

But depending on local regulations or how prone to being irritated your neighbors are, you may not really have the option of growing a female tree in the first place.

If you’re stuck with an unwanted female tree, you could look into growth-regulating sprays that prevent fruit set, such as this gallon of Florel Fruit Eliminator, available on Amazon.

Washington, DC has found success with this sort of treatment – thanks to a special clearance from the EPA, the city sprays its female ginkgos every year with a potato sprout inhibitor, which is harmless to humans but can make short work of fruiting.

But even if you manage to apply such a product across the entire crown once flowering starts – a tough endeavor, especially with large trees – fruit prevention is never a guarantee.

So if the fruit smell and litter of a female tree simply must go, then removing the tree is the only foolproof way.

A Battle of the (Ginkgo) Sexes

Speaking as a post-pubescent dude writing this, I’m well aware that boys often reek.

It’s an unfortunate aspect of being a human male, a putrid part of our nature that guys must suppress so that our society doesn’t smell like a sweaty pair of boxer shorts.

But the way that male ginkgos are less smelly than their female counterparts, across the board… I simply must tip my hat in respect. You did it, boys. You did the impossible.

Have any questions or comments to share? The comments section awaits.

Trying to learn more about other shade trees for the landscape? Metaphorically park a lawn chair underneath these guides: